APOL1 Genetic Risk: How African Ancestry Increases Kidney Disease Chance

21 Jan, 2026If you have recent African ancestry, your risk for kidney disease isn’t just about diet, blood pressure, or diabetes. A hidden genetic factor-APOL1-plays a major role in why kidney failure is so much more common in Black populations. This isn’t about race. It’s about ancestry, evolution, and biology.

What Is APOL1 and Why Does It Matter?

The APOL1 gene makes a protein that helps your body fight off a deadly parasite called Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense-the cause of African sleeping sickness. Around 5,000 to 10,000 years ago, certain changes in this gene, called G1 and G2 variants, gave people in West Africa a survival advantage. Those with the variants were more likely to survive the parasite and pass the gene on.

Today, those same variants are linked to kidney damage. The irony? The very genes that saved lives from infection now increase the risk of kidney failure. These variants are found in about 30% of people from West African countries like Ghana and Nigeria. They spread through the African diaspora, meaning they’re common in African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and others with recent African roots.

But here’s the catch: you need two copies of the risky variant to be at high risk. That means G1/G1, G2/G2, or G1/G2. Only about 13% of African Americans carry this high-risk combination. Still, among those who develop non-diabetic kidney disease, nearly half have these variants. That’s why APOL1 explains up to 70% of the extra kidney disease risk seen in people of African descent compared to others.

How APOL1 Damages the Kidneys

The APOL1 protein normally attacks trypanosomes by punching holes in their membranes. But in kidney cells, the same trick turns harmful. The risk variants make the protein too aggressive. It starts damaging the filtering units of the kidney-the glomeruli-leading to scarring and loss of function.

This damage shows up as specific kidney diseases:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

- Collapsing glomerulopathy

- HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN)

- Arterionephrosclerosis (kidney damage from high blood pressure)

One study found that nearly half of all end-stage kidney disease cases in people of African ancestry with HIV were directly tied to APOL1. That’s staggering. And it’s not just HIV. Other triggers-like viral infections, obesity, or uncontrolled blood pressure-can push the system over the edge.

Most People With APOL1 Risk Don’t Get Sick

Here’s what many don’t tell you: having two risky APOL1 variants doesn’t mean you’ll definitely get kidney disease. In fact, about 80 to 85% of people with the high-risk genotype never develop serious kidney problems. That’s called incomplete penetrance.

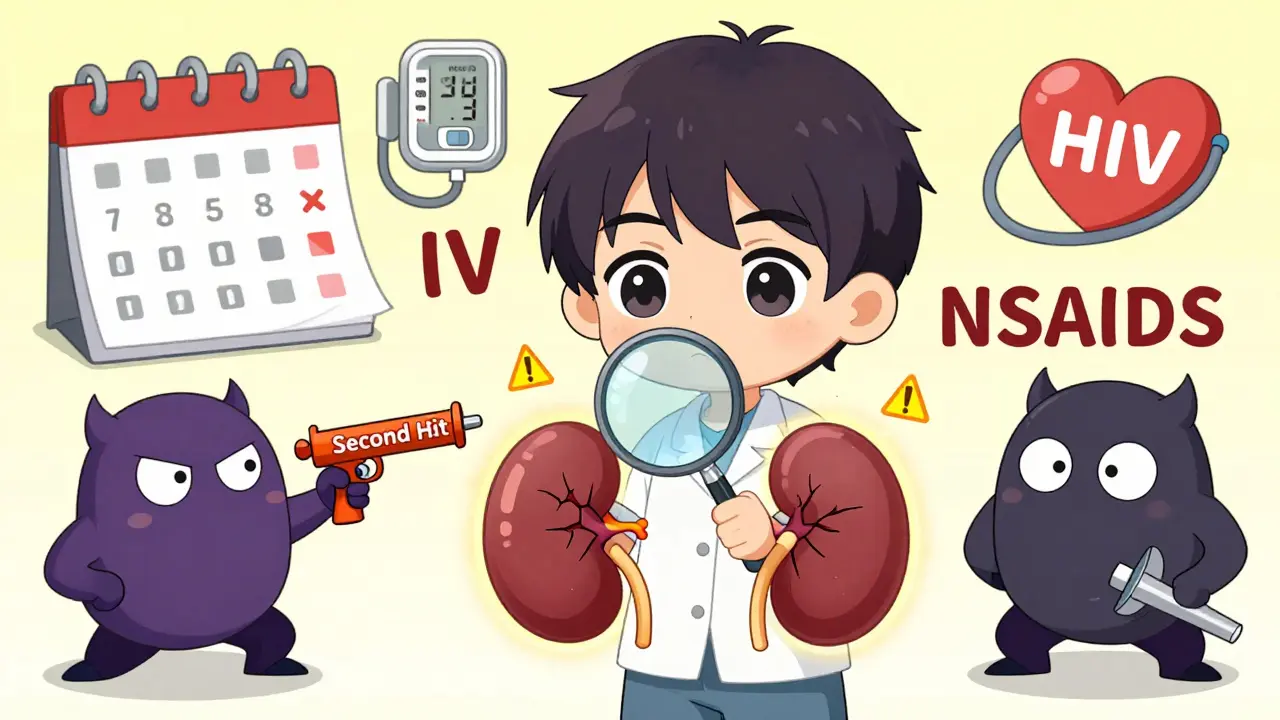

Think of it like a loaded gun. The gene is the gun. But something else-like HIV, COVID-19, or chronic high blood pressure-pulls the trigger. That’s why doctors call these other factors “second hits.”

That’s also why some people live into their 70s with the variants and never know it. Others, especially younger adults, get hit hard after a viral infection or pregnancy. The timing is unpredictable.

Testing for APOL1: Who Should Get It?

Genetic testing for APOL1 became available in 2016. Today, companies like Invitae and Fulgent Genetics offer it for $250 to $450 without insurance. It’s a simple blood or saliva test.

Current guidelines recommend testing for:

- People of African ancestry with kidney disease, especially if it’s not caused by diabetes or high blood pressure

- Living kidney donors with African ancestry-because donating could put them at higher risk if they carry the variants

- People with a family history of early kidney failure

But here’s the problem: many doctors still don’t know how to interpret the results. A 2022 survey found that 78% of nephrologists felt undertrained in counseling patients about APOL1. Patients often misunderstand their risk-thinking a positive result means kidney failure is certain. It’s not. It means higher risk. Like smoking increases lung cancer risk, but not everyone who smokes gets cancer.

What to Do If You Have High-Risk APOL1

If you’re found to have high-risk APOL1, you’re not doomed. You’re just more vulnerable. And that means you can take action.

Experts recommend:

- Annual urine test for albumin (a sign of early kidney damage)

- Regular blood pressure checks-with a target under 130/80 mmHg

- Avoiding NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen, which can stress the kidneys

- Controlling weight and avoiding smoking

- Getting vaccinated against viruses like HIV and COVID-19

One woman, Emani, found out she had the high-risk variants before any kidney damage. She started monitoring her urine and blood pressure yearly. Five years later, her kidney function is still normal. That’s the power of early awareness.

Why Race Doesn’t Explain This-Ancestry Does

You’ll hear people say “Black people have higher kidney disease rates.” That’s misleading. It’s not about skin color. It’s about genetic ancestry tied to West Africa.

These APOL1 variants are virtually absent in European, Asian, and Indigenous American populations. But they’re common in people whose ancestors came from Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, or other parts of West Africa-even if they now live in the U.S., Canada, or the UK.

That’s why the medical community is moving away from race-based kidney estimates. In 2022, the American Medical Association officially discouraged using race to adjust kidney function tests (eGFR). Why? Because APOL1 shows that biology, not skin color, drives risk.

New Treatments Are on the Horizon

For decades, there was no treatment targeting APOL1 itself. But that’s changing.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals is developing a drug called VX-147 that blocks the harmful APOL1 protein. In a 2023 trial of 140 patients, it reduced protein in the urine by 37% in just 13 weeks. That’s a big deal-protein in urine is a key sign of kidney damage.

The NIH has invested over $125 million in APOL1 research since 2020. A new 10-year study called the APOL1 Observational Study is tracking 5,000 people with the high-risk variants to better understand who gets sick and why.

By 2035, experts believe APOL1-targeted therapies could reduce kidney failure disparities by 25 to 35%. But only if access is fair. Right now, only 12% of low- and middle-income countries can test for APOL1. That’s a justice issue.

Real Stories, Real Impact

One Reddit user, ‘BlackMedStudent,’ writes: “I have the high-risk genotype. I check my blood pressure every week. I get my urine tested every year. It’s stressful, but I’d rather know than wonder.”

Another person on the National Kidney Foundation’s forum said: “My doctor told me I have a 1 in 5 chance of kidney failure. The uncertainty is worse than a diagnosis.”

Those stories show the emotional weight of this knowledge. But they also show the power of control. Knowing your risk lets you act.

What’s Next?

By 2026, guidelines will likely recommend routine APOL1 screening for all adults of African ancestry with high blood pressure or early signs of kidney damage. By 2027, efforts will focus on making testing affordable and accessible everywhere-not just in wealthy countries.

For now, if you have African ancestry and have kidney issues-or a family history of them-ask your doctor about APOL1 testing. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t assume it’s just high blood pressure. This is a genetic risk, and it’s real.

The science is clear: APOL1 is one of the strongest genetic links to kidney disease ever found. And for the first time, we’re not just watching the problem-we’re building solutions.

Can I get tested for APOL1 if I don’t have kidney disease?

Yes, but testing is usually recommended only if you have African ancestry and a personal or family history of kidney disease, especially non-diabetic types. For healthy individuals without symptoms, routine screening isn’t yet standard. However, if you’re considering being a living kidney donor, APOL1 testing is strongly advised.

Does having APOL1 risk variants mean I will definitely get kidney failure?

No. Only about 15-20% of people with two high-risk APOL1 variants will develop kidney disease in their lifetime. Most people live with the variants without ever having symptoms. The risk is increased, not guaranteed. Other factors like infections, high blood pressure, or obesity are often needed to trigger damage.

Is APOL1 testing covered by insurance?

Coverage varies. Some insurance plans cover APOL1 testing if it’s ordered by a nephrologist for diagnostic purposes, especially if you have unexplained kidney disease. For asymptomatic people or donors, coverage is less common. Out-of-pocket costs range from $250 to $450. The American Kidney Fund offers financial assistance for qualifying patients.

Can APOL1 affect kidney transplant outcomes?

Yes. If a person with high-risk APOL1 variants receives a kidney transplant from a donor without the variants, the transplanted kidney usually works fine. But if the donor has two risk variants, the new kidney may fail faster. That’s why living donors of African ancestry are now routinely tested before donation.

Are there any lifestyle changes that can lower APOL1-related risk?

Yes. Controlling blood pressure (target <130/80), avoiding NSAIDs like ibuprofen, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking, and managing viral infections (like HIV and COVID-19) can reduce the chance of kidney damage. Annual urine tests for protein and regular kidney function checks are key. Early detection gives you the best shot at preventing progression.

Why don’t all Black people have APOL1 risk variants?

Not all people with African ancestry carry the variants because they originated in specific regions of West Africa and spread through population migration. People with ancestry from East Africa, Southern Africa, or mixed backgrounds may not carry them. It’s not about race-it’s about specific ancestral lineage. Someone with Nigerian roots is more likely to carry them than someone with Ethiopian or South African roots.

Neil Ellis

January 22, 2026 AT 19:23This is one of those rare moments where science actually feels like justice - not just medicine, but history made visible. That gene? It’s a legacy of survival. Our ancestors fought a parasite that wiped out entire villages, and they won - with their DNA. Now we’re paying the price in kidneys, but damn, they earned every bit of that survival. I’m proud of them. And I’m mad that we’re only now catching up.

It’s not about race. It’s about lineage. It’s about West Africa’s quiet heroes who never got a medal, just a genetic fingerprint that outlived them. If we ever build a monument to resilience, APOL1 should be carved into it.

Alec Amiri

January 23, 2026 AT 09:54So let me get this straight - you’re telling me Black people are just genetically doomed to kidney failure? Cool. So what’s next? Are we gonna start testing babies at birth and stamp their diapers with ‘High Risk’? Just saying, this sounds like genetic determinism with a side of racism dressed up as science.

Lauren Wall

January 23, 2026 AT 17:13People like you are why this stuff stays dangerous. You reduce biology to a stereotype. APOL1 isn’t a Black thing - it’s a West African thing. Stop conflating ancestry with race. It’s lazy and harmful.

Lana Kabulova

January 24, 2026 AT 22:54Wait - so if you have two copies of G1 or G2 you’re at risk? But 80% of people with that never get sick? So… it’s not the gene, it’s the triggers? Then why are we even testing? Why not just tell everyone to avoid NSAIDs and control BP? Why make it a genetic panic?

Also - who’s paying for this? My cousin got tested and her insurance denied it. Now she’s stuck paying $400 to find out she might get sick someday? That’s not healthcare. That’s anxiety sales.

arun mehta

January 25, 2026 AT 09:45This is beautiful science 🌍✨

Our ancestors survived a deadly plague - and now, their gift is helping us fight a silent killer. It’s not a curse. It’s a legacy. And with new drugs like VX-147 coming, we’re turning survival into prevention.

Let’s not fear the gene - let’s honor it, understand it, and protect those who carry it. Knowledge is power - and power is responsibility. 🙏

Chiraghuddin Qureshi

January 26, 2026 AT 03:18From India to the African diaspora - we all carry hidden histories in our DNA. I never knew APOL1 existed until I read this. Now I’m telling everyone I know. This isn’t just a Black issue. It’s a human issue. 🙌🌍

Patrick Roth

January 26, 2026 AT 03:22Hold on - you’re saying APOL1 explains 70% of the disparity? But didn’t the 2020 study in JAMA show that socioeconomic factors account for over 60%? So why are we ignoring access to care, diet, pollution, stress? This feels like genetic scapegoating with a fancy name.

Tatiana Bandurina

January 27, 2026 AT 20:58It’s not about ‘risk’ - it’s about inevitability. If you have the variants, you’re ticking a time bomb. And doctors still don’t know how to explain it. People panic. Or they ignore it. Either way, it’s a disaster waiting to happen. And no one’s talking about the mental toll.

Keith Helm

January 28, 2026 AT 11:54APOL1 testing should be mandatory for all living kidney donors of African descent. Period. Not optional. Not ‘if you feel like it.’ This is standard of care. If you’re donating an organ, you need to know if you’re sacrificing your own kidney health. This isn’t controversial. It’s ethics.

Rob Sims

January 29, 2026 AT 19:23So you’re telling me I have a 1 in 5 chance of kidney failure? Cool. Thanks for the heads-up. Now what? I’m supposed to live in fear of ibuprofen and high blood pressure? Meanwhile, my white neighbor smokes three packs a day and never gets tested. Who’s really getting screwed here?