Medicaid Substitution Rules: Mandatory vs Optional by State

31 Dec, 2025Every year, thousands of children in the U.S. lose their private health insurance - not because their parents can’t afford it, but because their parent’s job changes, hours get cut, or an employer drops coverage. When that happens, many families turn to Medicaid or CHIP for help. But here’s the catch: in most states, they can’t get it right away. There’s a waiting period. And that’s not an accident. It’s by design.

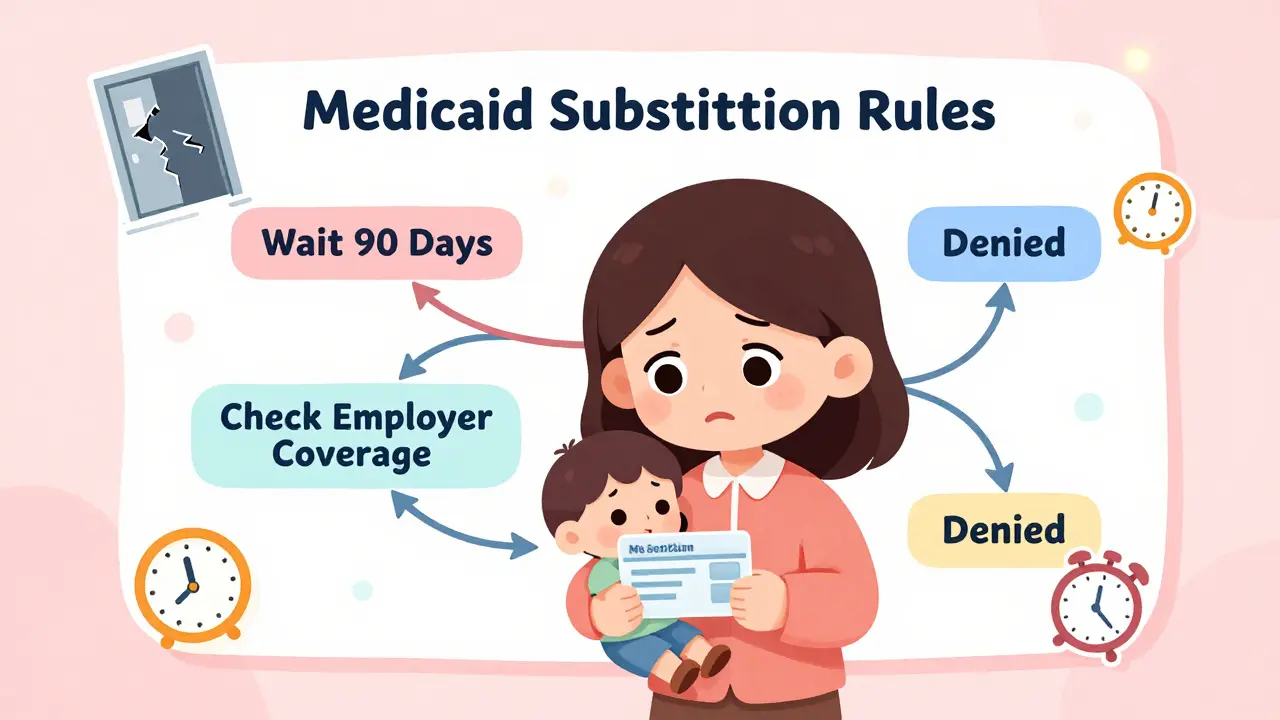

Why Medicaid Can’t Just Step In Right Away

Medicaid and CHIP aren’t meant to be first-choice insurance. Federal law says they’re supposed to be the last resort. That’s the core idea behind Medicaid substitution rules. These rules exist to stop families from dropping affordable private insurance just to get free public coverage. The goal? Keep private insurance markets strong and make sure public money goes to those who truly have no other options. The rule comes from Section 2102(b)(3)(C) of the Social Security Act, updated in 1997 and again in 2010 under the Affordable Care Act. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a requirement. All 50 states and D.C. must have systems in place to prevent Medicaid or CHIP from replacing coverage that’s already available and affordable. But here’s where things get messy: what counts as “affordable”? And how do you prove someone has access to it? That’s where states start to differ - and why some families get help fast while others wait months.The Mandatory Rule: What All States Must Do

Every state must follow one non-negotiable rule: they cannot enroll a child in CHIP if they’re eligible for affordable private coverage through a parent’s employer-sponsored plan. That’s the law. And to enforce it, states need to have procedures to check whether that coverage exists. The federal government doesn’t tell states how to do it - just that they must do it. So states built their own systems. Some use electronic databases to check if a parent’s employer offers insurance. Others call employers directly. A few still rely on paper forms and mailed documents. The result? A patchwork of approaches, all trying to answer the same question: Is private coverage available and affordable? Affordability is defined as premiums costing more than 9.12% of household income in 2024. If the cost is below that, the child is considered to have access to affordable coverage - even if the family hasn’t signed up yet. That’s a key detail. It’s not about whether they’re enrolled. It’s about whether they could be. States also have to make sure there’s a smooth transition if a family loses private coverage. If a parent’s job ends, the child can’t be stuck without insurance for 90 days while the state checks everything. That’s why the 2024 Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment Rule requires states to automatically enroll kids in CHIP if they lose private coverage - as long as they meet income rules. This rule took effect in April 2024, and states have until October 1, 2025, to fully implement it.The Optional Rule: Waiting Periods and State Choices

While the substitution rule itself is mandatory, how states enforce it isn’t. One major option states can choose: a waiting period. This is where things get personal for families. Under federal rules, states can require a family to wait up to 90 days before enrolling a child in CHIP after losing private coverage. The idea? Give the family time to get new employer insurance. But in practice, it often means kids go without care for months. Thirty-four states use this 90-day waiting period. That includes big states like California, Texas, and New York. In those places, a parent who loses a job on a Friday might have to wait until late January to get CHIP coverage for their child - even if they qualify financially. But 16 states don’t use waiting periods at all. Instead, they use real-time data sharing. Minnesota, for example, connects its Medicaid system directly to private insurers. When a parent’s coverage ends, the system flags it automatically. The child is enrolled in CHIP the same day - no paperwork, no waiting. That’s called the “Bridge Program.” It cut coverage gaps by 63%. Some states go even further. Fifteen states have added extra exemptions to the waiting period. If a parent loses their job, works fewer hours, or gets a pay cut, their child can get CHIP immediately - no 90-day wait. Florida, Illinois, and Pennsylvania are among them.How States Check for Private Insurance

Knowing whether a family has access to private insurance isn’t easy. And it’s not just about asking. The system has to verify. Twenty-eight states use electronic databases to check employer coverage. They pull data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ Health Insurance Resource Database. It’s fast. It’s accurate. But not all employers report to it. And some small businesses don’t even offer insurance - but still claim they do. Twenty-two states rely mostly on household surveys. That means asking parents to fill out forms, sign statements, or provide pay stubs. This method is slow. The average state takes 14.2 days to verify coverage. In the meantime, kids go without care. A Medicaid worker in Ohio described the problem this way: “We get families who lose employer coverage on Friday and need CHIP Monday. But the 90-day rule forces us to deny them for 12 weeks. They often end up uninsured during that time.” The 2024 rule tries to fix this by requiring states to accept eligibility determinations from other programs - like the Affordable Care Act marketplace. If a family applied for a marketplace plan and was denied because they were too poor, that’s proof they need CHIP. No more waiting.What Works: The States Getting It Right

Not all states struggle with substitution rules. Some have figured out how to protect private insurance without leaving kids uncovered. Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Oregon are the top performers. They all share three things: real-time data sharing, automatic enrollment, and seamless transitions between Medicaid and CHIP. In Minnesota, when a child loses private insurance, the system triggers an automatic CHIP enrollment. No forms. No delays. Coverage gaps dropped to under 8% - compared to the national average of 21%. These states also train their staff better. They don’t just rely on paperwork. They use technology to catch changes before families even ask for help. In contrast, Louisiana’s strict substitution rules in 2021 caused a 4.7 percentage point jump in uninsured children. Why? Because families gave up. They didn’t wait 90 days. They just didn’t enroll at all.The Hidden Cost: When Rules Backfire

Substitution rules were meant to save money. And they have. Since 2010, they’ve prevented about $1.3 billion in inappropriate CHIP spending each year. But the cost isn’t just financial. It’s human. Families who work hourly jobs, in agriculture, construction, or hospitality - industries with unstable hours - are hit hardest. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found that in states with strict substitution rules, more kids end up completely uninsured than enrolled in CHIP. Why? Because the system feels unfair. Parents think, “If I can’t get help even when I lose my job, why bother?” Joan Alker from Georgetown University calls it a penalty for working. “These rules punish families for having jobs that don’t offer stable insurance,” she says. “They’re not avoiding coverage - they’re being pushed out of it.” And then there’s the administrative burden. States spend an average of $487,000 a year just to run substitution checks. That’s money that could go to outreach, education, or better care.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The 2024 rule is the biggest shift in decades. By December 31, 2025, every state must have systems in place to automatically detect when private coverage ends and switch kids to CHIP - no waiting. States that haven’t updated their systems yet will face federal pressure. CMS now requires quarterly reporting on substitution-related coverage gaps. If a state has more than 15% of kids falling through the cracks, they’ll be asked to explain why. Industry analysts predict that by 2027, all states will use automated data matching. Manual verification will drop by 65%. That’s good news for families - but it means states need to invest now. The Congressional Budget Office says substitution rules will keep saving money through 2030. But the Urban Institute warns: if nothing changes, the rules will become useless. The insurance market is changing too fast. Short-term plans, gig work, and variable hours make the 1997 model outdated.What Families Should Know

If you’re a parent and your child loses private insurance:- Apply for CHIP immediately - don’t wait.

- Ask if your state has a waiting period. If they do, ask about exemptions (job loss, reduced hours, etc.).

- Don’t assume you’re ineligible just because you had coverage last month. You might still qualify.

- Check if your state uses automatic enrollment. Some do - and you might get enrolled without even applying.

- If you’re denied, appeal. Many denials are based on outdated or incorrect information.

Final Thoughts

Medicaid substitution rules aren’t good or bad. They’re complicated. They’re meant to protect public funds and private markets. But they’ve become a barrier for the very families they’re supposed to help. The 2024 update is a step forward. But real progress will come when states stop treating substitution as a paperwork problem - and start treating it as a care problem. The goal shouldn’t be to keep kids out of Medicaid. It should be to keep them covered - no matter where their parents work, how many hours they put in, or how often their insurance changes.What are Medicaid substitution rules?

Medicaid substitution rules are federal regulations that prevent Medicaid or CHIP from replacing affordable private health insurance. They require states to verify whether a child has access to coverage through a parent’s employer before enrolling them in public insurance. The goal is to preserve private insurance markets and target public funds to those without other options.

Is the 90-day waiting period mandatory for all states?

No. While all states must prevent substitution of private coverage, only 34 out of 50 states use the 90-day waiting period as a tool. The other 16 states use alternative methods like real-time data sharing with insurers or household surveys to determine eligibility without imposing a waiting period.

Can a family be denied CHIP even if they have no income?

Yes. If a child is eligible for affordable private coverage through a parent’s employer - even if the family isn’t enrolled in it - the state can deny CHIP enrollment. Affordability is based on premium cost relative to household income (over 9.12% in 2024), not whether the family is currently using the plan.

What changed with the 2024 Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment Rule?

The 2024 rule requires states to automatically enroll children in CHIP when they lose private coverage, eliminating the need for a 90-day waiting period in most cases. It also mandates real-time data sharing between Medicaid and CHIP programs and requires states to accept eligibility determinations from other insurance programs like the ACA marketplace. Implementation is required by October 1, 2025.

Which states have the most effective substitution rules?

Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Oregon have the most effective systems. They use real-time data matching with private insurers and automatic enrollment, reducing coverage gaps to under 8%. These states avoid long waiting periods and minimize bureaucratic delays, ensuring children stay covered during transitions.

Do substitution rules affect adult Medicaid enrollees?

No. Substitution rules apply only to children enrolled in CHIP or Medicaid under the CHIP program. Adult Medicaid eligibility is determined separately and is not subject to the same private insurance substitution requirements.

What happens if a parent declines employer coverage?

Even if a parent declines employer-sponsored insurance, the child may still be ineligible for CHIP if the coverage is considered affordable. The rule is based on availability, not enrollment. States can deny CHIP if the employer plan meets affordability standards, regardless of whether the family chose to enroll.

How can families appeal a substitution denial?

Families can request a fair hearing through their state’s Medicaid agency. They should gather documentation like pay stubs, termination letters, or proof of employer coverage costs. Many denials are overturned when incorrect or outdated information is corrected. States are required to provide appeal instructions when denying coverage.

Paul Ong

January 2, 2026 AT 00:16Kristen Russell

January 2, 2026 AT 09:32Richard Thomas

January 3, 2026 AT 17:34Lee M

January 4, 2026 AT 10:54Bryan Anderson

January 5, 2026 AT 17:14Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 6, 2026 AT 18:29Liam George

January 7, 2026 AT 14:37Donna Peplinskie

January 9, 2026 AT 07:43Olukayode Oguntulu

January 9, 2026 AT 21:20jaspreet sandhu

January 10, 2026 AT 02:26Alex Warden

January 11, 2026 AT 03:46LIZETH DE PACHECO

January 12, 2026 AT 21:58sharad vyas

January 13, 2026 AT 04:03Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 15, 2026 AT 03:22Dusty Weeks

January 16, 2026 AT 13:41