Ototoxic Medications: Understanding Drug Risks to Hearing and How to Monitor Them

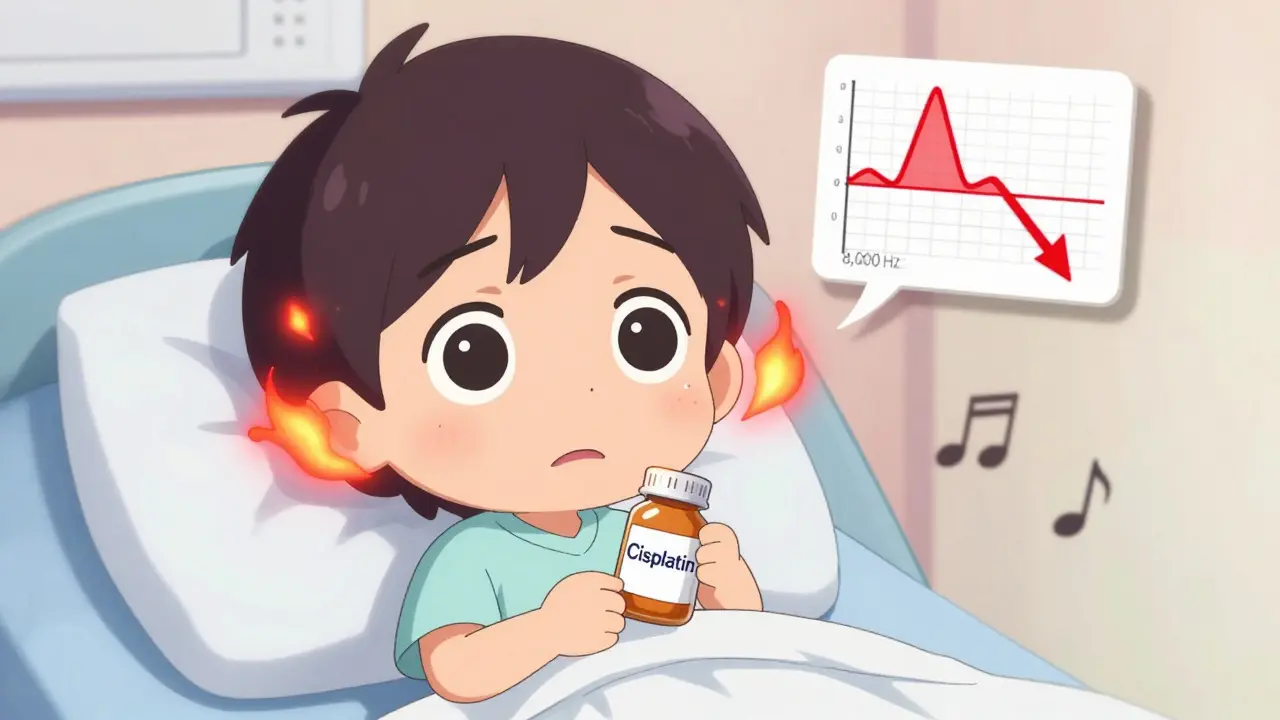

1 Feb, 2026Many people don’t realize that some of the most life-saving drugs can also quietly steal your hearing. Medications like cisplatin for cancer and gentamicin for serious infections are essential - but they come with a hidden cost: permanent damage to the inner ear. This isn’t rare. Around 600 prescription drugs are known to be ototoxic, meaning they harm the cochlea or vestibular system. For patients on long-term treatment, the risk isn’t just theoretical - it’s real, measurable, and often preventable.

How Ototoxic Drugs Actually Damage Your Ears

Your inner ear is packed with tiny hair cells that turn sound waves into electrical signals your brain understands. These cells don’t regenerate. Once they’re gone, the hearing loss is permanent. Ototoxic drugs don’t just affect your ears randomly - they target these cells with precision. Aminoglycoside antibiotics like gentamicin and amikacin trigger oxidative stress. They flood the cochlea with free radicals, basically burning out the hair cells from the inside. Cisplatin, a chemotherapy drug, does something even more insidious: it builds up in the cochlea and keeps damaging cells for months after treatment ends. Other drugs, like some antidepressants (amitriptyline, sertraline), interfere with neurotransmitters that help the ear communicate with the brain. Some reduce blood flow to the inner ear, starving the hair cells of oxygen. The damage usually starts at the high frequencies - between 4,000 and 8,000 Hz. That’s why people first notice trouble hearing birds chirping, children’s voices, or the ‘s’ and ‘th’ sounds in speech. By the time standard hearing tests (which only go up to 4,000 Hz) show a problem, the damage is already advanced.High-Risk Medications and Who’s Most Affected

Not all ototoxic drugs are created equal. Some carry far higher risks than others.- Aminoglycosides (gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin): Used for severe infections like drug-resistant TB or sepsis. Between 20% and 63% of patients on multi-day courses develop permanent hearing loss. The longer the treatment, the higher the risk.

- Cisplatin: The most ototoxic chemotherapy drug. Between 30% and 60% of patients experience hearing loss, with 18% suffering severe or profound loss. Kids are especially vulnerable - up to 35% show language delays due to undiagnosed hearing damage.

- Carboplatin and Oxaliplatin: These are alternatives to cisplatin with much lower ototoxicity (5-15% and under 5% respectively), but they’re not always as effective against certain cancers.

- Some antidepressants: Tricyclics and SSRIs like fluoxetine and sertraline can cause tinnitus or temporary hearing changes, especially at high doses.

Genetics also play a role. A small number of people carry a mitochondrial DNA mutation (m.1555A>G) that makes them 100 times more likely to lose hearing from a single dose of gentamicin. But routine genetic screening isn’t standard yet - it’s still debated whether it’s cost-effective for the general population.

Why Standard Hearing Tests Miss the Danger

Most doctors order a basic audiogram - 250 Hz to 4,000 Hz. That’s fine for detecting age-related or noise-induced hearing loss. But it’s useless for catching ototoxicity early. Ototoxic damage starts at 8,000 Hz and above. If your test doesn’t go that high, you’re flying blind. A patient on cisplatin might lose hearing at 6,000 Hz after their third cycle - a red flag no standard test would catch. That’s exactly what one Reddit user reported: “My oncologist said my hearing was fine. Then I couldn’t hear my daughter’s voice on the phone. Turns out, I lost 40 dB at 6,000 Hz.” Standard tests also don’t check for tinnitus or balance issues - two early warning signs. Tinnitus (ringing, buzzing, hissing) is often the first symptom of cisplatin toxicity. Balance problems - feeling dizzy, unsteady, or nauseous - can signal vestibular damage from aminoglycosides.

How to Monitor Ototoxicity - The Right Way

Early detection saves hearing. Studies show that with proper monitoring, the risk of severe hearing loss drops by 30-50%. Here’s what works:- Baseline audiometry before treatment: Must include high frequencies (up to 12,000 Hz). No exceptions.

- Regular high-frequency testing: For cisplatin, test after each cycle. For aminoglycosides, test after every dose or every 2-3 days on long courses.

- Otoacoustic emissions (OAE): This test checks the health of outer hair cells before they show up on an audiogram. It’s 25% more sensitive than standard testing and can catch damage weeks earlier.

- Vestibular testing: For patients on high-dose aminoglycosides, balance tests (like VNG) should be part of the protocol.

- Track symptoms daily: Patients should log tinnitus, dizziness, or muffled hearing. Even small changes matter.

Coordination is key. Oncologists, infectious disease doctors, and audiologists need to talk. In centers with integrated care teams, severe hearing loss rates drop by 32%. Yet only 45% of U.S. cancer centers have formal ototoxicity monitoring programs - despite clear guidelines from ASHA and the American Academy of Audiology.

What’s New in Prevention and Treatment

There’s real hope on the horizon. In November 2022, the FDA approved sodium thiosulfate (Pedmark) to protect children with liver cancer from cisplatin-induced hearing loss. In trials, it cut the risk by 48%. It’s not a cure-all - it’s only approved for kids with localized tumors - but it’s the first drug ever approved specifically to prevent ototoxicity. Researchers are testing other otoprotective agents like N-acetylcysteine (an antioxidant) for aminoglycoside users. Early results are promising. Smartphone apps are also emerging. Scientists at Oregon Health & Science University are developing apps that use headphones to test hearing at 8,000-12,000 Hz. If they work, patients could monitor their hearing at home - making testing accessible even in rural areas. The Ototoxicity Working Group is updating its guidelines in mid-2024. One major change? Stronger recommendations for genetic testing in patients with family history of hearing loss after antibiotic use.

The Human Cost - Real Stories Behind the Numbers

Behind every statistic is a life changed. A mother on cisplatin for ovarian cancer started hearing a constant high-pitched ring after her second infusion. “I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t focus on my kids. I thought I was going crazy.” It took three months and a specialist audiogram to confirm it was ototoxicity - and by then, the damage was done. A teenager treated for Ewing’s sarcoma with cisplatin didn’t realize his hearing was fading until he failed a school hearing test. His teachers thought he was daydreaming. He’d missed months of classroom instruction. A man treated with gentamicin for a UTI developed permanent tinnitus. “It’s always there - louder at night. I had to quit my job because I couldn’t concentrate. No one warned me.” These aren’t outliers. They’re common.What You Can Do

If you’re prescribed a high-risk medication:- Ask: “Is this drug known to affect hearing?”

- Insist on a baseline audiogram that includes 8,000-12,000 Hz - before treatment starts.

- Ask if your care team has an ototoxicity monitoring plan. If not, request one.

- Track symptoms: tinnitus, dizziness, muffled hearing. Write them down.

- Don’t assume your doctor knows. Many don’t. Be your own advocate.

If you’re a caregiver or parent of a child on cisplatin: push for monitoring. Pediatric hearing loss can derail language, learning, and social development. Early detection changes everything.

The good news? We have the tools. We know how to catch it. We have drugs that can help. The problem isn’t science - it’s systems. Too many patients slip through the cracks because no one asked the right questions.

You deserve to be heard - literally. Don’t let a life-saving drug steal your ability to hear your loved ones, your favorite music, or the quiet moments in between.

Which medications are most likely to cause hearing loss?

The highest-risk medications include aminoglycoside antibiotics like gentamicin and amikacin, and platinum-based chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin. Cisplatin affects 30-60% of patients, with up to 18% developing severe or profound hearing loss. Other ototoxic drugs include certain antidepressants (amitriptyline, sertraline), loop diuretics (furosemide), and quinine. Always ask your doctor if your prescription is on the list of known ototoxic agents.

Can ototoxic hearing loss be reversed?

No. Once the hair cells in the inner ear are destroyed, they do not regenerate. The hearing loss is permanent. That’s why early detection is so critical - stopping the drug or reducing the dose as soon as damage is detected can prevent further loss, but it won’t restore what’s already gone.

Why don’t doctors always check for hearing loss during treatment?

Many doctors aren’t trained to recognize ototoxicity risks or don’t have access to the right testing equipment. Standard hearing tests only go up to 4,000 Hz, but ototoxic damage starts at 8,000 Hz and above. Without high-frequency audiometry and otoacoustic emissions testing, early signs are invisible. Also, monitoring requires coordination between specialists - something not all clinics have in place.

Is there a genetic test to see if I’m at higher risk?

Yes. A mutation in mitochondrial DNA (m.1555A>G) makes people extremely sensitive to aminoglycosides - up to 100 times more likely to lose hearing after one dose. Testing exists, but it’s not routine because it’s expensive and only useful for people with a family history of hearing loss after antibiotic use. Experts recommend testing if you or a close relative had sudden hearing loss after taking gentamicin or streptomycin.

What should I do if I notice ringing in my ears during treatment?

Don’t ignore it. Tinnitus is often the first sign of ototoxic damage. Tell your doctor immediately. Request a high-frequency audiogram and otoacoustic emissions test. Do not wait until you feel like you’re missing conversations. Early intervention can stop further damage - even if the ringing doesn’t go away, you can prevent total hearing loss.

Are there alternatives to cisplatin or gentamicin?

Sometimes. For cancer, carboplatin or oxaliplatin are less ototoxic alternatives to cisplatin, though they may be less effective for certain tumors. For infections, newer antibiotics like colistin or tigecycline may be options instead of gentamicin - but they have their own side effects. The decision depends on your condition, infection type, and cancer stage. Always discuss alternatives with your specialist - don’t assume there are none.

Gary Mitts

February 3, 2026 AT 05:02clarissa sulio

February 5, 2026 AT 00:04Brittany Marioni

February 6, 2026 AT 08:35Monica Slypig

February 6, 2026 AT 15:14Becky M.

February 7, 2026 AT 14:49jay patel

February 8, 2026 AT 21:47Eli Kiseop

February 8, 2026 AT 22:43Nick Flake

February 10, 2026 AT 09:25Akhona Myeki

February 10, 2026 AT 10:44Sandeep Kumar

February 11, 2026 AT 22:06Chinmoy Kumar

February 12, 2026 AT 23:08Brett MacDonald

February 13, 2026 AT 01:01