Why the First Generic Drug Filer Gets 180 Days of Market Exclusivity

10 Dec, 2025When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, a race begins-not for speed, but for paperwork. The first company to file a generic version with the right legal paperwork gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic drug. No one else can enter the market during that time. Why does this matter? Because in the world of pharmaceuticals, those 180 days can mean hundreds of millions in revenue-and for patients, it can mean faster access to cheaper medicine.

How the 180-Day Clock Starts

The rule isn’t arbitrary. It comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act, passed in 1984. Before this law, generic drug makers couldn’t even start testing their versions until the brand-name patent expired. That meant years of waiting. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It let generic companies file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) while the brand patent was still active-but only if they challenged it. That challenge is called a Paragraph IV certification. It’s a legal notice saying: "We believe this patent is invalid, or our drug won’t infringe it." The first company to file an ANDA with this certification gets the 180-day exclusivity prize. But here’s the twist: the clock doesn’t always start when the FDA approves the drug. It can start earlier-if a court rules in the generic company’s favor on the patent dispute. That means a company could win a lawsuit in January, and even if the FDA hasn’t approved the drug yet, the 180-day clock starts ticking.Why This Incentive Exists

Filing a Paragraph IV certification isn’t cheap. It costs between $5 million and $10 million in legal fees, patent analysis, and litigation prep. Most small companies can’t afford it. Only big players like Teva, Mylan, or Sandoz regularly take the risk. So why would anyone spend millions to challenge a patent? Because the reward is huge. During those 180 days, the first generic filer has no competition. They can capture 70-80% of the market. For a popular drug like Lipitor or Copaxone, that’s billions in sales. Teva made $1.2 billion in just six months when it launched the first generic of Copaxone in 2015. That’s the power of exclusivity. The government designed it this way on purpose. The goal was to speed up access to low-cost drugs. Without this incentive, few companies would risk the legal battle. The brand-name drug company could drag out litigation for years, and generics might never show up. Hatch-Waxman flipped the script: it gave generics a reason to fight-and win.

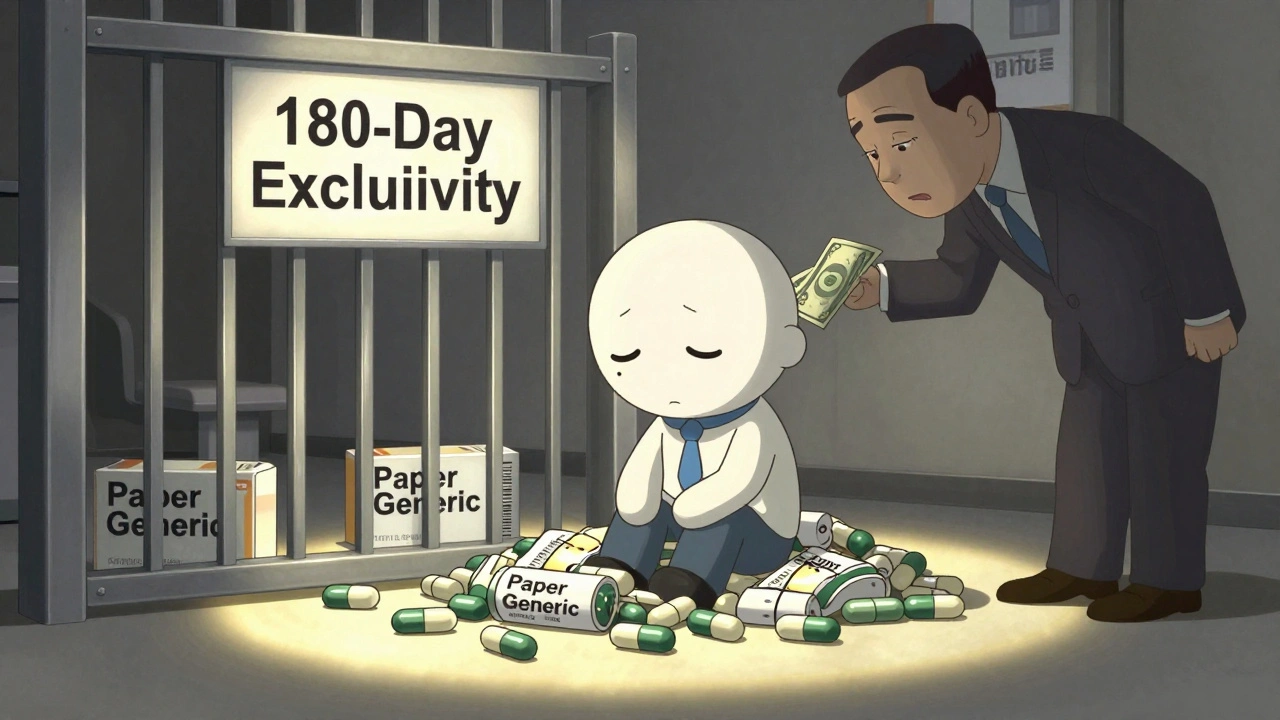

The Problem: When the Clock Runs, But No One Sells

Here’s where things go wrong. Sometimes, the first filer wins the court case, the 180-day clock starts, but they never actually sell the drug. Maybe they’re waiting for the right price. Maybe they made a deal with the brand company to delay entry. This is called a "paper generic"-a company that holds exclusivity but doesn’t launch. The FDA can’t approve any other generic until that 180 days are up-even if the first filer sits on the approval for years. In some cases, this has delayed generic competition for over two years. IQVIA found that since 2010, 45% of first filers either delayed launch or never launched at all. That’s not competition. That’s a loophole. Brand companies have exploited this. They sometimes pay the first generic filer millions to delay entry-a "reverse payment." One former brand executive anonymously admitted on Reddit that paying $50 million to delay a generic for 18 months was cheaper than losing 100% of sales overnight. The FTC estimates these deals cost consumers $3.5 billion a year.How the System Is Changing

The FDA noticed. In 2022, they proposed a major fix: the 180-day exclusivity clock should only start when the generic drug is actually sold-not when a court rules. That way, if a company wins a lawsuit but doesn’t launch, the clock doesn’t tick. Other generics can enter immediately. This change would end the "paper generic" problem. It would also stop brand companies from using legal delays as a shield. The FDA calls this "modernizing Hatch-Waxman" to match its original intent: get affordable drugs to patients faster. But the brand drug industry is pushing back. PhRMA argues that changing the rule might discourage generic companies from filing challenges at all. If the reward isn’t guaranteed, why spend $10 million on a lawsuit? The Congressional Budget Office disagrees. They estimate that keeping the old system will cost Medicare $13 billion less in savings over ten years than adopting the new rule. That’s billions in savings for patients, insurers, and taxpayers.

Who Benefits-and Who Gets Left Out

The current system benefits big generic manufacturers. They have the lawyers, the cash, and the patience to play the long game. Small companies? They rarely make it. Only 15% of small generic firms even use the FDA’s free guidance resources, mostly because the process is too complex. Patients benefit when generics arrive. In the U.S., generics make up 90% of all prescriptions-but only 22% of drug spending. That’s how much money this system saves. But when the first filer doesn’t launch, patients wait. And wait. And wait. The FDA’s 2023 Strategic Plan for Competitive Generic Therapies (CGT) offers another path. CGT exclusivity doesn’t rely on patent challenges. It’s granted to the first generic to market a drug with little or no competition, and the clock only starts when sales begin. It’s simpler. It’s fairer. And it’s growing.What’s Next for Generic Drugs?

The 180-day exclusivity rule isn’t going away. But it’s being reshaped. The FDA’s proposed reforms, if passed, could bring 40-50 more generic drugs to market each year, saving consumers $1.2 to $1.8 billion annually. For now, the race still goes to the first filer. But the finish line is changing. It’s no longer about who files first-it’s about who sells first. That’s the real win for patients.What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement filed with the FDA by a generic drug company claiming that a brand-name drug’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by the generic version. It’s the key step that triggers eligibility for 180-day market exclusivity under the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Can more than one company get 180-day exclusivity?

Yes, but only if multiple companies file their ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications on the exact same day. In those cases, they can share the 180-day period. But if one files even one day earlier, they get the full exclusivity. That’s why filing times are tracked down to the second.

Why do brand companies pay generic makers to delay entry?

Brand companies pay generics to delay because losing 100% of their market share overnight can cost billions. Paying $20-50 million to delay entry for a year or two is often cheaper than losing revenue fast. These deals, called "reverse payments," are controversial and often challenged by the FTC.

What’s the difference between 180-day exclusivity and CGT exclusivity?

The 180-day exclusivity is tied to patent challenges and can start with a court ruling-even if the drug isn’t sold. CGT exclusivity is for drugs with little or no generic competition and only starts when the generic is actually marketed. CGT doesn’t require a patent fight, making it simpler and less prone to manipulation.

How long does it take to file a successful Paragraph IV application?

Preparing a Paragraph IV certification typically takes 18-24 months. It requires deep patent analysis, legal strategy, and financial readiness. The FDA rejects about 37% of these filings due to technical errors, so precision matters.

What happens if the first filer doesn’t launch the drug?

Under current rules, the 180-day clock still starts (often after a court win), and no other generic can enter until the period ends-even if the first filer never sells the drug. This creates a "blockade" that delays competition. The FDA’s proposed reform would fix this by tying exclusivity to actual market entry.

Is the 180-day exclusivity rule unique to the U.S.?

Yes. The U.S. is the only country that grants 180-day market exclusivity based on patent challenges. Other countries rely on different systems to encourage generic entry, such as faster approval timelines or price controls, but none offer this specific legal incentive.

Jean Claude de La Ronde

December 12, 2025 AT 06:56so like... the system is basically a poker game where the first guy to bluff wins a million bucks and then just sits on the hand forever? 🤔

we pay lawyers to fight over paper patents so someone can sit on a drug like it's a collectible card?

bruh. this isn't capitalism. this is monopoly with a pharmacy license.

Jim Irish

December 13, 2025 AT 13:56The Hatch-Waxman Act was a landmark compromise that balanced innovation and access.

Today’s abuses are not flaws in the design but failures in enforcement.

Reforming the clock to start at market entry aligns with the original intent.

Patent challenges should incentivize entry, not delay.

Mia Kingsley

December 14, 2025 AT 12:41OMG I JUST READ THIS AND I'M SO MAD

like why do big pharma get to pay off generics to NOT sell stuff???

and also why is the FDA even letting this happen??

IT'S LIKE THEY'RE ON THE SIDE OF THE BRANDS

AND ALSO I SAW A POST ON TWITTER THAT SAID TEVA DID THIS WITH LIPITOR AND NOW I'M CRYING

WHY IS EVERYTHING SO BROKEN??

Kristi Pope

December 14, 2025 AT 21:50It's wild how something meant to help patients ended up becoming a game only the richest players can win.

But honestly? I’m still glad we have generics at all.

My grandma’s blood pressure med costs $4 now because of this system.

Maybe we just need to fix the loopholes instead of scrapping the whole thing.

Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Small companies need more support-not less hope.

And maybe if the FDA gave free legal help to indie generics, we’d see more real competition.

It’s not perfect, but it’s not hopeless either.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 16, 2025 AT 00:43Man, I never thought about how much psychology goes into this.

It’s not just law or money-it’s timing, ego, fear.

Big companies play chess while small ones are still trying to find the board.

But honestly? The fact that we even have this system is kinda beautiful.

Someone had to say: ‘Hey, what if we made it worth it for the underdog to fight?’

Even if it got corrupted… the idea was good.

Maybe we just need to reset the rules, not the goal.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

December 16, 2025 AT 11:19The FDA’s proposed reform is scientifically and economically sound.

Linking exclusivity to market entry eliminates strategic delay tactics.

Studies from the Congressional Budget Office confirm significant cost savings.

Reverse payments are anticompetitive and have been ruled illegal in multiple jurisdictions.

PhRMA’s argument lacks empirical support and ignores the public health imperative.

Patients deserve timely access, not corporate negotiation games.

Courtney Blake

December 17, 2025 AT 14:24AMERICA IS BROKEN.

THEY LET CORPORATIONS BUY TIME LIKE IT'S A COMMODITY.

WHY DO WE STILL ALLOW THIS?

THEY'RE NOT EVEN HIDING IT.

THEY'RE BRAGGING ABOUT IT ON REDDIT.

AND WE CALL THIS A DEMOCRACY?

MY TAX DOLLARS PAY FOR THESE DRUGS.

AND THEY'RE BEING STOLEN.

JUST SHUT IT DOWN.

JUST. SHUT. IT. DOWN.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 19, 2025 AT 01:57So let me get this straight.

You’re telling me the whole system is just a way for big pharma to pay off the first generic company to not compete?

And we call this innovation?

And the FDA is fine with this?

And people still act like this is a free market?

Wow.

Just wow.

Nothing new.

Just more proof the system is rigged.

Eddie Bennett

December 19, 2025 AT 01:59Yeah I’ve seen this play out with my uncle’s meds.

He waited two years for a generic that never came.

Meanwhile the brand kept raising prices.

It’s not about patents anymore.

It’s about who can outlast who.

And patients? We’re just the ones stuck in the middle.

But I’m kinda hopeful about the FDA’s new rule.

Maybe if we tie the clock to actual sales, it’ll force real competition.

Not just legal theater.

Vivian Amadi

December 19, 2025 AT 16:14THEY’RE NOT EVEN TRYING TO HIDE IT.

THEY JUST PAID $50 MILLION TO DELAY A GENERIC.

AND YOU CALL THIS CAPITALISM?

IT’S FEUDALISM WITH A PHARMACEUTICAL LICENSE.

AND YOU’RE ALL JUST SITTING THERE LIKE IT’S NORMAL?

WE NEED TO BURN THE SYSTEM DOWN.

AND START OVER.

NO MORE EXCLUSIVITY.

NO MORE LAWSUITS.

JUST DRUGS.

FOR PEOPLE.

WHY IS THIS SO HARD?

Ariel Nichole

December 20, 2025 AT 10:29I just want to say thank you to everyone who fights for these reforms.

It’s easy to feel powerless when big companies win.

But this post? It’s a roadmap.

And honestly? I feel a little less alone knowing people are trying to fix this.

Keep going.

john damon

December 21, 2025 AT 07:46